Passages en Passant #5:

Lucie Havel & Dico Kruijsse / Carolin Lange

December 1, 2022 – Januari 19, 2023

Het interview

(english below)

door Heyer Turnheer

Lucie Havel, Carolin Lange en Dico Kruijsse waren uitgenodigd om samen een tentoonstelling te realiseren in de corridor tentoonstellingsruimte ‘Passages en passant’ bij Goethe-Institut Rotterdam in februari 2023. De huidige gang- en ruimte-installatie in relatie tot de bijzondere ruimtelijke omstandigheden is waar we het hier over willen hebben. Op de linkermuur zien we ongeveer duizend kleine objecten in verschillende bruintinten, die de ruimtelijke uitlijning van de gang met toenemende spreiding volgen; we zien daar ook een boek liggen. Aan de rechterkant zien we papieren vlakken en stroken in verschillende formaten in de fijnste tinten blauw, die de ruimte bepalen, aan en voor de muur hangen en het licht van bovenaf de ruimte in leiden.

Heyer: Laten we jullie werken voorstellen, Lucie, Carolin en Dico. Ik vond online een samenvattende notitie van Lucie, waarin ze zegt dat haar werk gebaseerd is op een interesse in de mens en diens relatie met de natuur. En inderdaad, in je muurinstallatie hier in het Goethe-Institut vinden we precies deze modus terug: in je gedachten die je in het boek presenteert en in de manier waarop je een plant hanteert om er kneedbaar materiaal uit te halen. En over Carolin en Dico vertelde het internet me dat het uitgangspunt van jullie werk ligt in het experimentele veld van blauwdrukken; de blauwdruk als een ontwerp- of schetspraktijk gebaseerd op analoge fotografie. Trouwens, zal ik met jullie, Carolin en Dico, praten als collectief, of als individuele, samenwerkende kunstenaars?

Carolin: We zijn geen collectief, we zijn toevallig twee mensen die samenwerken….

Dico: We noemen het ‘Under the same Sun’ als we dit gezamenlijke werk doen. Voor de rest werken we individueel, ja.

Heyer: Oké. Laten we dan beginnen met jullie werken hier in de tentoonstelling te ondervragen. Lucie, jouw project is gebaseerd op het omgaan met de Japanse duizendknoop. Zoals de term al zegt, is het een onkruid en dus iets met negatieve connotaties. In je publicatie staat dat je werk op de een of andere manier een positieve manier is om met een vijand om te gaan, toch? Kun je ons iets vertellen over dit materiaal-genererende proces en hoe je deze tentoonstelling hebt opgebouwd?

Lucie: De op Japanse duizendknoop gebaseerde materialen van het project ‘How I Fell in Love with the Enemy’ zijn allemaal het resultaat van een vraag: Kan ik me aanpassen aan mijn omgeving in plaats van de omgeving aan te passen aan mijn behoeften, zoals de maatschappelijke norm is? Deze vraag kwam bij me op toen ik begon met het aanleggen van een tuin bij mijn studio. Het aanleggen van een tuin houdt in dat je bestaande planten vervangt voor de planten die er je wilt laten groeien. Het bleek dat ik dit deed zonder enige kennis van de wilde planten in de tuin en wat ze voor mij zouden kunnen betekenen. Ik probeerde verschillende dingen met verschillende planten, zoals het maken van papier, kneedmassa, kleur en dat soort dingen. Een van deze planten was Japanse duizendknoop. Ik begon het te koken en soda toe te voegen, waardoor het een volledig rode kleur kreeg. Tijdens deze eerste fase van het werk rees de vraag of ik deze invasieve plant op dezelfde wijze wilde bestuderen zoals de westerse samenleving dat doet, namelijk, door ze te exploiteren. Maar toen ik dit ongelooflijke basismateriaal zag, zijn karakteristieke structuur en kleurschakeringen, wilde ik er iets mee doen, ook met het doel om de plant vanuit een ander perspectief te laten zien. Zo ontstond het werk dat je hier in de tentoonstelling ziet.

Heyer: En hoe is het verder gegaan?

Lucie: Ik heb veel verschillende materialen en kleurstoffen gemaakt van de duizendknoop. Voor de tentoonstelling in het Goethe-Institut maakte ik drieëntwintig verschillende soorten van deze op pulp gebaseerde vormmassa. Hiervoor kookte ik de pulp van de planten met verschillende hoeveelheden soda. In latere experimenten voegde ik ook boekweitmeel en kalk toe. Ik gebruikte zowel de bladeren als de stengels van de plant. Voor het huidige werk heb ik dit materiaal met mijn handen gevormd tot de objecten die hier te zien zijn, met een sterk maar eenvoudig gebaar.

Heyer: Wow, wat een verhaal en maatschappelijk statement, Lucie, dank je wel! We zullen later verder praten over je werk. Maar eerst hebben we ook een statement van Carolin en Dico nodig. Ik wil hun werk ook graag introduceren. Kunnen jullie het publiek vertellen wat een blauwdruk is? In deze tentoonstelling zien we blauwe kleur op papier. Maar hoe is het gemaakt? Het publiek kan zich afvragen: is het misschien een drukwerk? Wat is het, dit fotografische blauwdrukonderzoek dat je doet en welke werkprocessen hebben geleid tot jullie tentoongestelde werken?

Carolin: Het project is begonnen vanuit een nieuwsgierigheid om experimentele manieren van blauwdrukken te verkennen en om in en met architecturale ruimtes te werken – maar ook vanuit een interesse in hoe je licht kunt vangen op een schaal van 1:1, en hoe je licht kunt vastleggen met camera-loze fotografie. Maar laten we hiermee beginnen: er zijn veel verschillende opvattingen en ideeën over een blauwdruk. Het uitgangspunt van ons project was het allereerste begin van de blauwdruktechniek, een fotografische studie uit de jaren 1840. Dus echt aan het begin van de vroege fotografie. Er was een wetenschapper, John F.W. Herschel, die planten en verschillende materialen uitgebreid testte op lichtgevoeligheid. Binnen deze systematische experimenten stuitte hij toen bijna op het blauwdrukproces. Eén ingrediënt, dat toen nieuw was, kreeg hij van een collega; het andere ingrediënt was overal verkrijgbaar. Hij realiseerde zich toen dat in reactie met licht, het mengsel van beide ingrediënten een diepblauw pigment creëert. Hij deelde het proces vrijelijk met anderen en stelde het voor als een fotografisch afdrukproces. Ik vind het echt intrigerend, dit idee van ‘licht vangen’ of ‘licht schrijven’ met fotografische reacties.

Dico: Met ons project begonnen we te experimenteren met het vastleggen van licht in verschillende ruimtes en op verschillende materialen door gebruik te maken van dit vroege blauwdrukproces, dat overigens zijn naam ontleent aan de architectuur. Voor architecten was het vanaf de jaren 1880 een erg handige techniek om hun plannen te kopiëren. In ons project brachten we deze chemicaliën aan op een vel papier en belichtten we dit papier ergens in de zon. Het is een soort registratie van licht en schaduwen in een bepaalde landelijke of architecturale ruimte. We hadden zelfs het idee om het op de gevel van een gebouw te doen, heel groot, maar dat project hebben we om verschillende redenen opgegeven.

Heyer: Ik begin het te begrijpen. Het is een lichtgevoelige oplossing die je op een oppervlak aanbrengt en dan blootstelt aan licht, zoals wat er gebeurt als een fotograaf in de donkere kamer werkt met licht op fotogevoelig papier, toch?

Dico: Ja. Maar in tegenstelling tot moderne donkere kamer chemie, produceert het geen giftig afval. Dit element is belangrijk voor ons, in termen van duurzamere manieren van werken; het is niet schadelijk voor de natuur, noch voor je handen. Dat is nog een reden waarom we er graag mee werken.

Heyer: Klinkt voor mij eerlijk in de oren. En wat de technische kant betreft, als ik het goed begrijp, wordt een oppervlak dat met deze specifieke emulsie is beschilderd of bespoten en in het zonlicht of ander licht wordt geplaatst, lichter of donkerder blauw, afhankelijk van de intensiteit van het licht en de duur van de blootstelling aan het licht, toch? En dan probeer je plekken te vinden met intrigerende lichtomstandigheden, zoals een bos of een stedelijke plek, of in je studio, of in een gang of waar dan ook.

Dico: Voor een deel is dit blauwdrukproject voortgekomen uit de interesse om het architectuurboek ‘Learning from Las Vegas’ (van Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown uit 1972) te lezen. Door over de gebouwen in Las Vegas te praten en verschillende architecturale situaties met elkaar te vergelijken en een beetje architectuurtheorie te bedrijven, is het boek een zeer kritische reactie. Het zegt dat deze gebouwen in Las Vegas zo raar zijn omdat ze niet in de situatie passen, en ze zijn ook allemaal verschillend van elkaar; ze delen niets. Er is maar één ding dat ze verbindt, ze staan onder dezelfde zon. De zon schijnt op hen allemaal, op dezelfde manier, elke dag. Dus daar hebben we de titel van onze gecoproduceerde blauwdrukprojecten, alle verschillende werken werden gerealiseerd onder dezelfde zon. Het is een soort verbindend iets. Plaatsen en gebouwen gezien in de realiteit van de alledaagse interactie met licht – de zon die opkomt en ondergaat – dit maakt het als het ware opmerkelijk. Elk raam waar de zon naar binnen schijnt is anders, maar dit fenomeen van daglicht gebeurt overal op aarde. Dus we dachten, het is leuk dat je dit soort super-intieme, privémomenten van licht hebt die je kunt vangen met de blauwdrukchemicaliën. We besloten voor precies deze lichtmomenten te gaan en te proberen ze vast te leggen.

Heyer: Klinkt fascinerend, geweldig verhaal. Een andere, meer technische vraag: Toen jullie de werken maakten die we hier in de tentoonstelling zien, hoe controleerden jullie toen het lichtproces dat het oppervlak van het papier met de tijd donkerder en donkerder maakte? Hoe beheerden jullie dit tijdschema en hoe stopten jullie het proces?

Dico: Je moet min of meer raden wanneer het klaar is. En dan moet je het fixeren met water, wat soms ook sporen achterlaat. Je weet nooit precies wanneer het klaar is, wanneer het de kleurtoon heeft die je wilt. Het is altijd een beetje giswerk.

Carolin: Je moet werken met het zonlicht van de dag, met de steeds veranderende richting van de zon en de lichtintensiteit van de dag. Je moet je goed voorbereiden en je voortdurend bewust zijn van wat er om je heen gebeurt. Wanneer we het licht rechtstreeks in een architecturale omgeving of in architecturale maquettes registreren, begrijpen we de binnenkant van een gebouw als een donkere kamer, een camera obscura, een plaats met een ingang, waar het licht binnenkomt en waar het doorheen reist.

Heyer: Bedankt voor deze introductie tot jullie blauwdrukproject, Carolin en Dico. Ik zou jullie ook willen vragen om jullie verhalen te delen over het omgaan met de specifieke ruimte van de tentoonstelling, de gang, en natuurlijk hoe jullie met elkaar omgaan. Als voorbeeld: Kenden jullie elkaar al eerder?

Lucie, Dico en Carolin: Nee, eigenlijk niet. We hebben elkaar leren kennen door deze tentoonstelling.

Heyer: Hoe zijn jullie elkaar tegengekomen en hebben jullie elkaars werk leren kennen?

Lucie: Ik zag het werk van Carolin en Dico op de website van Kunstambassade en dacht: Wow, dit is echt interessant. Wat ik meteen leuk vond aan hun werk was een soort open proces waarbij je niet alles onder controle hebt en ook niet alles wilt controleren. Het materiaal en vooral het licht hebben een soort “agency”, een handelingsmogelijkheid, in het uiteindelijke werk. Wat me ook opviel was de kleur van dit specifieke blauw. Dus besloot ik om mijn werk aan dat van hen aan te passen, door dit bruine materiaal te gebruiken dat ik uit Japanse duizendknoop heb gehaald en dat prachtig contrasteert met dit specifieke blauw dat op het blauw van de lucht lijkt. Ik bedacht twee elementen die me heel natuurlijk leken. Daarna bezocht ik Carolin’s studio om meer te weten te komen over hoe zij werkt.

Heyer: En in termen van ruimte, hoe heb je bijvoorbeeld besloten om je werk links of rechts van de gang te installeren? Hoe is dat besluitvormingsproces verlopen?

Lucie: In eerste instantie dacht ik aan het architectonisch toe-eigenen van de gang met zijn interessante hoeken. Toen ik hoorde dat Carolin en Dico van plan waren om verschillende blauwdrukken en schilderijen te presenteren, ben ik van gedachten veranderd en heb ik gekozen voor een installatie op één muur als reactie op hun werk. Toen ontstond het idee van een lange rij handgrote objecten die zich over de hele gangmuur uitstrekken, dicht opeen opgehangen in het lagere deel van de gang en meer verspreid in het hogere deel van de ruimte.

Carolin: Ja, het was al heel vroeg duidelijk dat de linkerkant gewoon de meest geschikte plek is voor het werk van Lucie. En ja, we waren ook heel blij toen we hoorden dat we een tentoonstelling met Lucie konden doen. We zagen haar absoluut fascinerende onderzoek en werk op haar website. Ik was meteen overdonderd door de prachtige kleurovergangen van de bruine objecten, die ze uit Japanse duizendknoop haalt. En toen we elkaar in de studio ontmoetten, hadden we al ideeën over hoe we op haar werk zouden reageren met een serie blauwe kleurverlopen. Deze kleurverlopen zijn toen speciaal voor deze tentoonstelling gemaakt en om op Lucie te reageren.

Heyer: En waar heb je deze nieuwe blauwdrukwerken gerealiseerd? Hier, in de tentoonstellingsruimte?

Dico: Nee, niet echt. Voor deze tentoonstelling bleek dat onmogelijk; het was te bewolkt op de dagen dat we tijd en toegang tot de ruimte hadden. Dit is een probleem dat we vaak hebben en we hebben een paar strategieën ontwikkeld om ermee om te gaan. De drie grote werken aan het begin van de gang met de kleurverlopen zijn speciaal voor deze ruimte gemaakt, maar we hebben ze hier niet gerealiseerd. We hebben ze buiten Carolins atelier gemaakt, op de stoep. Een ander werk dat we hier laten zien was gebaseerd op een specifieke lichtsituatie die zich soms voordoet in Carolins studio; om precies te zijn in de hal aan de voorkant, waar de zon door een reeks ramen en glazen deuren schijnt. Gedurende ongeveer vijftien minuten tijdens zonsondergang in oktober maakt het heel bijzondere vormen. We hebben geprobeerd om hier ter plekke een afdruk van te maken, maar het licht was te zacht om sporen achter te laten, dus hebben we de licht-en-schaduw situatie nagebootst met hout en karton in de felle juli-zon. Een ander nieuw werk dat we hier laten zien begon met een kleine maquette van het dakraam van de tentoonstellingsruimte in het Goethe-Institut. We hebben dit model misschien een week lang blootgesteld aan licht op het dak van Carolins studio, ik kan me niet alle details herinneren. Het is de foto met alle verplaatste driehoeken. En de andere delen van de installatie zijn schilderijen die ik in mijn atelier heb gemaakt.

Carolin: Ja, we zijn gefascineerd door hoe licht zich verplaatst en hoe we deze beweging zichtbaar kunnen maken als een blauwdruk. Door licht gedurende weken en maanden op te nemen, realiseer je je hoe de zon door de ruimte reist en hoe de aarde in de loop van de tijd om de zon draait. De resultaten van deze langdurige lichtopnames, die hier ook worden tentoongesteld, zijn in zekere zin heel abstract. Voor een serie werken gebruikte Dico deze ‘opnames’ en maakte er schilderijen van op grote schaal, met hetzelfde blauwe pigment.

Dico: We waren erg enthousiast over hoe ons werk zou passen bij het werk van Lucie. Ik denk dat we er alle drie naar streefden om een nieuwe heelheid te bereiken in de setting van ons materiaal, van de individuele delen van Lucie’s werk en dat van onszelf; Lucie met dit monumentale gebaar, en wij met onze uitwaaierende bewegingen in de ruimte.

Heyer: Lucie, je hebt het al eerder gezegd, je bent hier begonnen in de gang met het lage plafond en zonder licht van buitenaf. Tegen het einde van de gang wordt het plafond steeds hoger en culmineert in een opening met een dakraam. Je installatie volgt deze logica op de voet. Heb je het onafhankelijk van het werk van Carolin en Dico geïnstalleerd, nadat jullie samen de eerste beslissingen hadden genomen?

Lucie: Na de eerste ontmoeting en algemene discussie hebben we een beslissing genomen over de indeling van de ruimte. Het was een heel gemakkelijk besluitvormingsproces; we waren het er allemaal over eens dat mijn werkidee beter paste op de linkermuur met de hoeken en randen, en dat hun werk perfect paste bij de bijzondere lichtsituatie aan de rechterkant van de gang. Het was voor ons allemaal duidelijk dat deze oplossing het beste zou werken. Met mijn installatie heb ik geprobeerd het verloop van de gang te volgen. Dat was een uitdaging, want de gang heeft veel zeer specifieke vormen en het plafond en de vloer lopen niet parallel. Dus om de aandacht te vestigen op deze karakteristieke vormen, besloot ik dat de installatie een enkele, brede, horizontale lijn zou zijn.

Heyer: En ook om de verschillende delen van de muur met elkaar te verbinden door de specifieke plaatsing van je werk, toch?

Lucie: Ja. En ook om de verticaliteit van de vele handgrote objecten te compenseren.

Dico: Lucie had inderdaad te maken met deze sterke verticale sneden in de architectuur van de linkermuur.

Heyer: Jullie, Carolin en Dico, hebben jullie blauwdrukinstallatie ontworpen volgens de logica van de gang, maar meer in termen van licht. Hoe hoger het plafond wordt en hoe dichter het bij dat briljante moment komt waarop het licht door dat grote dakraam naar binnen valt, hoe feller het wordt. Deze elementen snijden de muur ook in afzonderlijke stukken, niet architectonisch, maar in verschillende lichtsecties.

Dico: Met betrekking tot Lucie’s installatie van het werk, hebben we onze plek stap voor stap opgebouwd aan de hand van het licht en de verschillende hoogtes van het plafond, ja.

Carolin: We bewonderden echt de setting van Lucie’s werk. Het heeft een rechtlijnige beweging die zelfs over de radiator heen gaat. Op die manier weerspiegelt het het onverbiddelijke, invasieve karakter van de plant dat Lucie’s kernmateriaal is, waarvan ze deze zwerm handgrote objecten in hun brede kleurenspectrum heeft gemaakt.

Lucie: En dat alles leidde er uiteindelijk toe dat we min of meer naast elkaar gingen werken in de tentoonstellingsruimte, nietwaar?

Dico: Ja, we probeerden verschillende dingen uit en bleven alles herschikken, om te zien wat past.

Carolin: Weet je, aan het begin van zo’n proces, als je elkaar nog niet zo goed kent, begin je elkaar meteen vragen te stellen als: Waar denk je aan? En op die manier wordt de setting steeds duidelijker.

Lucie: Vanaf het begin was ik erg gegrepen door de manier waarop Carolin en Dico hun werken ophingen, stap voor stap, in relatie tot het licht. Sommige werken gaan als het ware zelfs hoger dan de lijn van het plafond, de lichtschacht in; sommige werken strekken zich echt uit naar het licht. En dit feit lijkt deze gang volledig te openen. Zelfs de schaduwen van de werken op de muur, die verwijzen naar de vele verschillende formaten papier met de verschillende tinten blauw, zijn vol schoonheid. Het was prachtig om dit alles te zien op het moment van de realisatie.

Dico: Het was niet ons plan om zo hoog te gaan hangen… het gebeurde gewoon zo. Het was een poging. Iemand stond op de ladder, iemand hield het vast, en toen zei iemand: ‘Oh, het is geweldig zo, laten we het gewoon ophangen.’

Carolin: Dit was een prachtig moment van het installatieproces samen met Lucie, en er zijn er nog veel meer waar we het over zouden kunnen hebben.

Heyer: Stel je voor dat je gevraagd was om een tentoonstelling op te zetten in een white-cube ruimte, wat denk je dat er anders zou zijn gegaan?

Lucie: Het is heel grappig, want in een heel veilige white-cube zou het niet zo interessant zijn geweest als hier, waar we met de architectuur moesten omgaan en ermee moesten spelen.

Dico: Ik weet het niet, misschien hadden we het dan meer over de inhoud gehad. Want de situatie vroeg om vrij pragmatisch handelen. Er is een bepaalde karakteristieke specificiteit van de ruimte die vereist dat je kijkt naar wat van je werk past, en misschien minder naar wat je wilt laten zien en in de schijnwerpers wilt zetten.

Lucie: Daar ben ik het mee eens; als we in een white-cube zaten, zouden we waarschijnlijk meer hebben samengewerkt aan concepten. Ik weet het niet. Het zou vanaf het begin anders zijn geweest, dat weet ik zeker.

Carolin: De gang maakt beide werken meer privé, denk ik, omdat je die white-cube afstand tussen de werken niet hebt. Het bevorderde eerder een gesprek tussen de werken.

Lucie: Ja, absoluut, Carolin, en zoals je zegt, het is ook heel anders om een ruimte binnen te komen en voor de objecten te staan, of om er gewoon langs te lopen als je door een gang loopt en de objecten in het voorbijgaan te zien, vanaf de zijkant, zoals het gebeurt in deze gangsituatie.

Heyer: Bedankt voor al jullie observaties en opmerkingen, Lucie, Carolin en Dico, ik heb ons gesprek echt gewaardeerd. En bedankt, Kathrin en Marco, voor het organiseren ervan.

Heyer Thurnheer is een contextueel kunstenaar, activist en Filosofie van de Vrijheid socioloog met een multimediale kunstpraktijk. Hij is oprichter en lid van verschillende kunst- en onderwijscollectieven en tentoonstellingsplatforms in Zwitserland en Nederland. Zijn werk en geschriften worden regelmatig getoond in niet-institutionele kunstruimtes en openbare instellingen.

Lucie Havel, The progression (werktitel) installation, organic material, lime, 1540x95cm, 2022

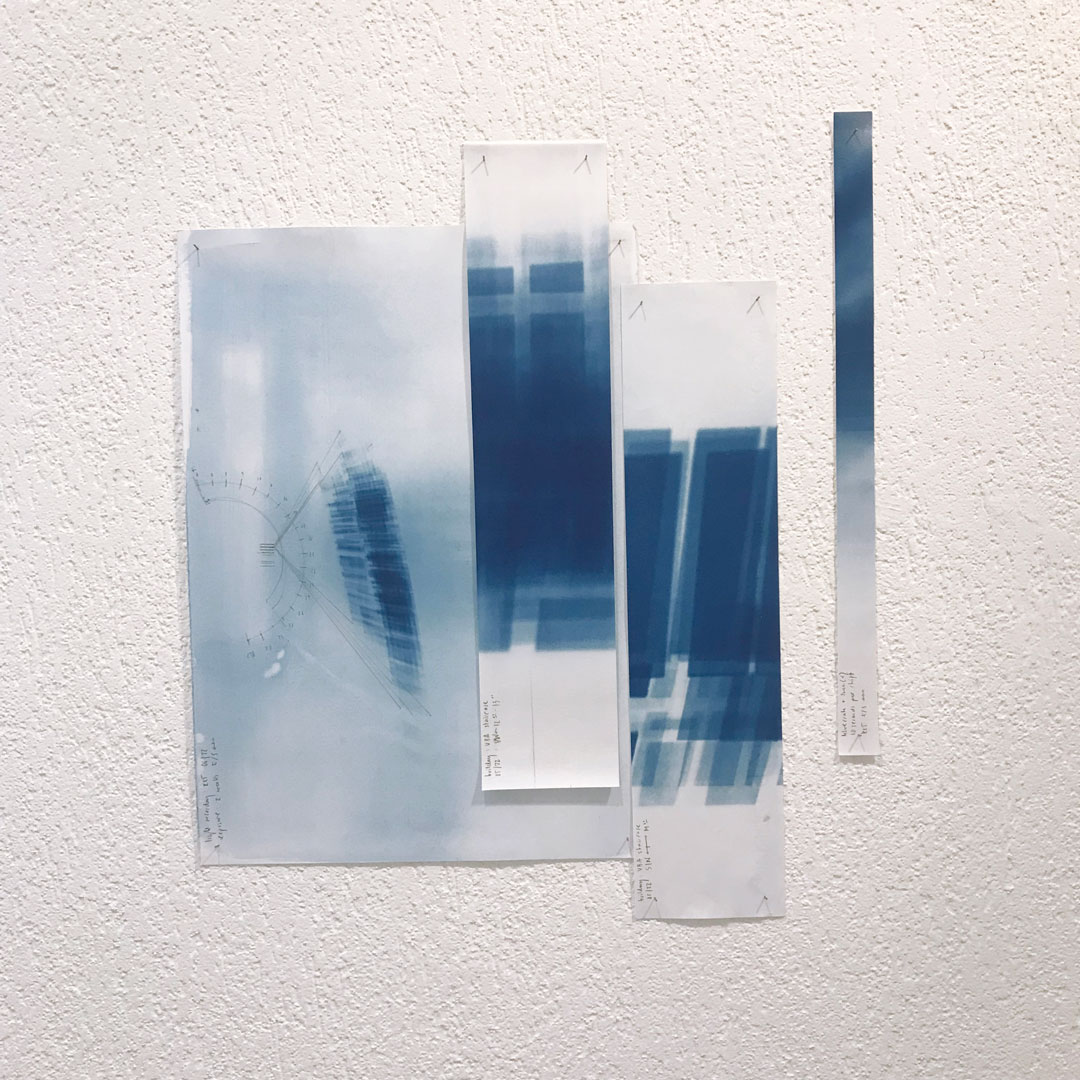

Dico Kruijsse/Carolin Lange, [Collage van het werkproces], cyanotype on paper, 50x40cm

Overzicht tentoonstelling met links werk van Lucie en rechts van Carolin / Dico

Overzicht tentoonstelling met links werk van Carolin / Dico en rechts van Lucie

The interview

by Heyer Turnheer

Lucie Havel, Carolin Lange and Dico Kruijsse were invited to realize an exhibition together in the corridor exhibition space ‘Passages en passant’ at Goethe-Institut Rotterdam in February 2023. The current corridor- and space installation set in relation to the particular spatial conditions is what we want to talk about here. On the left wall we see about a thousand small objects in different shades of brown, following the spatial alignment of the corridor at increasing spread; we also see a book lying there. On the right-hand side we see paper surfaces and strips in various formats in the finest shades of blue, determining the space, hanging on and in front of the wall, leading the light from above into the room.

Heyer: Let’s introduce your works, Lucie, Carolin and Dico. I found a summarizing note by Lucie online, saying that her work is based in an interest in the human and its relationship with nature. And indeed, in your wall installation here at Goethe-Institut, we find exactly this mode again: in your thoughts presented in the book and in the way you handle a plant to extract a mouldable material. And about Carolin and Dico, the Internet told me the starting point of your work lies in the experimental field of blueprints; the blueprint as a design or sketching practice based on analogue photography. By the way, shall I talk to you, Carolin and Dico, as a collective, or as singular, collaborating artists?

Carolin: We’re not a collective, we happen to be two people that work together…

Dico: We call it ‘Under the same Sun’ when we do this collaborative work. For the rest we work individually, yeah.

Heyer: Okay. So let’s start then by questioning your works here in the exhibition concretely. Lucie, your project is based on dealing with the Japanese knotweed plant. As the term says, it’s a weed, and as such, something with negative connotations. Your publication says that your work is somehow a positive way of dealing with an enemy, right? Can you tell us a little bit about this material-generating process and how you went about building up this exhibition ?

Lucie: The Japanese knotweed-based materials from the ‘How I Fell in Love with the Enemy’ project are all the result of a question: Can I adapt to my environment instead of adapting the environment to my needs, as is the societal norm? This question came to me when I started to create a garden at the studio. Creating a garden involves replacing existing plants with the plants you want to grow. It seemed to me that I was doing this without any knowledge of the wild plants in the garden and what they might mean to me. I tried various things with different plants, such as making paper, moulding compound, colour and other things like that. One of these plants was Japanese knotweed. I started by cooking it and adding soda, which gave it this completely red colour. During this first phase of work, the question arose as to whether I wanted to study this truly invasive plant by doing what Western society does, that is, exploiting it. But when I saw this incredible basic material, its characteristic structure and shades of colour, I wanted to do something with it, also with the aim of showing the plant in a different light. That’s how the work you see here in the exhibition came about.

Heyer: And how did it continue?

Lucie: I made a lot of different materials and dyes from knotweed. For the exhibition at the Goethe-Institut, I made twenty-three different types of this pulp-based moulding compound. To do this, I cooked the pulp of the plants with varying amounts of soda. In later experiments, I also added buckwheat flour and lime. I used the leaves of the plant as well as the stems. For the current work, I used my hands to shape this material into the objects shown here, with a strong but simple gesture.

Heyer: Wow, what a story and societal statement, Lucie, thank you! We will continue this talk about your work later. But first we need a statement from Carolin and Dico, too. I would like to introduce their work, too. Can you tell the audience what a blueprint is? In this exhibition, we see blue colour on paper. But how is it made? The audience may ask: Is it maybe a printed matter? What is it, this photographic blueprint research that you do and and which work processes led to your exhibited works?

Carolin: The project started out of a curiosity to explore experimental ways of blueprinting, and to work in and with architectural spaces – but also out of an interest in how to catch light at a 1:1 scale, and how to record light with camera-less photography. But let’s start first with this: there are many different understandings and ideas about a blueprint. The starting point of our project was the very beginning of the blueprint technique, a photographic study from the 1840s. So really at the beginnings of early photography. There was a scientist, John F. W. Herschel, who extensively tested plants and different materials for photosensitivity. Within these systematic experiments he then almost stumbled upon the blueprint process. He got one ingredient, which was new at the time, from a colleague; the other ingredient was widely available. He then realized that in reaction with light, the mixture of both ingredients creates a deep blue pigment. He freely shared the process with others and proposed it as a photographic printing process. I find it really intriguing, this idea of ‘catching light’ or ‘inscribing light’ with photographic reactions.

Dico: With our project, we started to experiment to record light in different spaces and on different materials by using this early blueprint process, which, by the way, has its name from architecture. For architects, it was a really handy technique to copy their plans from the 1880s onwards. In our project, we were just putting these chemicals onto a sheet of paper and then lighting this paper somewhere in the sunshine. It’s a kind of recording of light and shadows in a particular rural or architectural space. We even had the idea to do it on the facade of a building, very big, but we abandoned that project for different reasons.

Heyer: I am starting to understand. It is a light-sensitive solution that you put on a surface and then expose to light, like what happens when a photographer works in the darkroom with light on photo-sensitive paper, right?

Dico: Yeah. But unlike modern darkroom chemistry, it is doesn’t produce toxic waste. This element is important to us, in terms of more sustainable ways of working; it doesn’t harm nature, nor your hands. That is another reason we like to work with it.

Heyer: Sounds fair to me. And on the technical side, if I understand right, a surface painted or sprayed with this particular emulsion and set in the sunlight or any other light would turn lighter or darker blue, depending on the intensity of light and the duration of the exposure to light, right? And then you try to find places with intriguing light conditions, like a forest or an urban place, or in your studio, or in a corridor or wherever.

Dico: In part, this blueprint project grew out of the interest in reading the architecture book ‘Learning from Las Vegas’. In talking about the buildings in Las Vegas and comparing different architectural situations, and making a bit of architecture theory, the book is a very critical response. It says that these buildings in Las Vegas are so weird because they don’t fit in the situation, and they’re all different from each other too; they do not share anything. There is only one thing that connects them, they are under the same sun. The sun shines on all of them, in the same way, every day. So there we’ve got the title of our co-produced blueprint projects, all the different works were realized under the same sun. It’s this sort of unifying thing. Places and buildings seen in the reality of the everyday interaction with light – the sun rising and setting – this makes it sort of outstanding. Every window where the sun shines in is different, but this phenomenon of daylight happens everywhere on earth. So we thought, it’s nice that you have this sort of super-intimate, private moment of light that you can catch with the blueprint chemicals. We decided to go for exactly these moments in light and to try capturing them.

Heyer: Sounds fascinating, great story. Another, more technical question: When you were making the works we see here in the exhibition, how did you control this lighting process that made the surface of the papers darker and darker with the time? How did you manage this timetable and how did you stop the process?

Dico: You have to guess, more or less, when it’s ready. And then you have to fix it with water, which sometimes also leaves traces. You never know exactly when it’s finished, when it’s the tone of colour that you want. It always involves some guess-work.

Carolin: You have to work with the sunlight of the day, with the ever-changing direction of the sun and the light-intensity of the day. You have to prepare well and constantly be aware of what’s happening around you. When we record light directly in an architectural setting or in architectural scale models, we understand the inside of a building as a dark chamber, a camera obscura, a place with an entrance, into which light enters and in which it travels.

Heyer: Thank you for this introduction to your blueprint project, Carolin and Dico. I’d also like to ask you to share your stories about dealing with the particular space of the exhibition, the hallway, and, of course, how you interact with each other. As an example: Did you know each other before?

Lucie, Dico and Carolin: No, we really didn’t. We got to know each other through this exhibition.

Heyer: How did you come to meet and get to know each other’s work?

Lucie: I saw Carolin and Dico’s work on the Kunstambassade website and thought: Wow, this is really interesting. What I immediately liked about their work was this sort of open process where you don’t control everything and you don’t want to control everything. The material and especially the light have a kind of agency in the final work. What also struck me was the colour of this particular blue. So I decided to adapt my work to theirs, using this brown material that I extracted from Japanese knotweed and which contrasts magnificently with this particular blue that looks like the blue of the sky. I thought of two elements that seemed very natural to me. I then visited Carolin’s studio to find out more about how she works.

Heyer: And in terms of space, how did you decide, for example, whether to install your work on the left or the right side of the corridor? How did that decision-making process take place?

Lucie: At first I thought of appropriating the corridor architecturally with its interesting angles. And then, when I heard that Carolin and Dico had in mind to present diverse blueprints and paintings, I changed my mind and decided for a one single-wall installation as a response to their work. Then the idea came up of a long line of hand-sized objects stretching all along the corridor wall, hung in a denser mode in the lower part of the corridor and in a more spreading mode in the higher part of the room.

Carolin: Yes, it was clear very early that the left side is simply the most appropriate place for Lucie’s work. And yes, we were also very happy when we heard that we could do an exhibition with Lucie. We saw her absolutely fascinating research and work on her website. I was immediately overwhelmed by the wonderful colour gradients of the brown objects, which she extracts from Japanese knotweed. And when we met in the studio, we already had some ideas of how we would respond to her work with a series of blue gradients. These gradients were then created especially for this exhibition and to respond to Lucie.

Heyer: And where did you realize these new blueprint pieces? Right here, in the exhibition space?

Dico: No, not really. For this show it turned out to be impossible; it was too cloudy on the days that we had time and access to the space. This is a problem we have quite often, and we have developed a few strategies to deal with it. The three large works at the beginning of the corridor with the colour gradients were made especially for this room, but we did not realize them here. We did them outside of Carolin’s studio, on the sidewalk. Another work we show here was based on a specific light situation that sometimes happens in Carolin’s studio; to be precise, in the front hallway , where the sun shines trough a series of windows and glass doors. For about fifteen minutes during sunset in October it makes very particular shapes. We tried to make a print of this on site, but the light was too soft to leave any traces, so we recreated the light-and-shade situation with wood and cardboard in strong July sunshine. Another new work we are showing here started with a small maquette of the skylight area of the exhibition space at Goethe-Institut. We exposed this model to light for a week, maybe, on the roof of Carolin’s studio, I can’t remember all the details. It’s the picture with all the displaced triangles. And the other parts of the installation are paintings that I made in my studio.

Carolin: Yeah, we are fascinated by how light travels and how we can make this movement visible as a blueprint. Recording light over weeks and months, you realize how the sun travels in space and over time, how the earth rotates around the sun. The results of these long-duration light recordings, also exhibited here, are very abstract, in a way. For one series of works, Dico used these ‘recordings’ and turned them into large-scale paintings, using the same blue pigment.

Dico: We were very exited about how our work would fit with Lucie’s work. I think all three of us then aimed to achieve a new wholeness in the setting of our material, of the individual parts of Lucie’s work and our own; Lucie with this monumental gesture, and us with our fanning out in the space.

Heyer: Lucie, you already mentioned it before, you started here in the corridor with the low ceiling and no external light. Towards the end of the corridor the ceiling gets higher and higher and culminates in an opening with a skylight window. Your installation follows this logic closely. Did you install it independently from the work of Carolin and Dico, once you made your first decisions together?

Lucie: Well, after the first meeting and general discussion, we decided about the division of the space. It was a very easy-going decision-making process; we all agreed that my work idea fitted better on the left wall with the corners and edges, and their work fitted perfectly with the particular light situation on the right-hand side of the corridor. It was obvious to all of us that this solution would work best. With my installation I tried to follow the flow of the corridor. It was challenging, because the corridor has a lot of very specific shapes, and the ceiling and the floor are not parallel. So to draw attention to these characteristic shapes, I decided that the installation would be a single, wide, horizontal line.

Heyer: And also to connect the different parts of the wall through the particular placement of your work, right?

Lucie: Yes. And also to compensate for the verticality of the many hand-sized objects.

Dico: Indeed, Lucie had to deal with these strong vertical cuts in the architecture of the left-hand wall.

Heyer: You, Carolin and Dico, designed your blueprint installation according to the logic of the corridor, but more in terms of light. The higher the ceiling gets and the closer it gets to that brilliant moment when the light comes in from the ceiling through that big sky window, the brighter it turns. These features also cut the wall into separate pieces, not architecturally, but into different sections of light.

Dico: In reference to Lucie’s installation of the work, we kind of built up our site step by step according to the light and the different heights of the ceiling, yes.

Carolin: We really admired the setting of Lucie’s work. It has this rectilinear movement that even goes over the radiator. In that way, it mirrors the unrelenting, invasive character of the plant that is Lucie’s core material, from which she created this swarm of hand-sized objects in their wide spectrum of colours.

Lucie: And all of that finally led us to work more or less side by side in the exhibition space, didn’t it?

Dico: Yeah, we tried different things and kept rearranging everything, to see what fits.

Carolin: You know, at the beginning of a process like this, when you don’t yet know each other that well, you immediately start asking each other questions like: What are you thinking about? And in that way, the setting becomes clearer and clearer.

Lucie: From the beginning I was very taken by the way Carolin and Dico hung their works, step by step, in relation to the light. Some works even go higher than the line of the ceiling, into the shaft of light, so to speak; some works really stretch towards the light. And this fact seems to open up this corridor completely. Even the shadows of the works on the wall, referring to the many different-sized papers with the different shades of blue, are full of beauty. It was wonderful to see all of this in the moments of its realization.

Dico: It wasn’t our plan to go that high with the hanging… it just happened that way. It was an attempt. Somebody was on the ladder, somebody was holding it, and then somebody said, ‘Oh, it’s great this way, let’s just hang it.’

Carolin: This was a wonderful moment of the install process together with Lucie, and there are many others we could talk about.

Heyer: Imagine you had been asked to set up an exhibition in a white-cube space, what do you think would have gone differently?

Lucie: It’s very funny, because in a very safe white cube it wouldn’t have been as interesting as here, where we had to deal with with the architecture and played it.

Dico: I don’t know, maybe we would have talked more about the content, then. Because the situation called for quite pragmatic action. There’s this given characteristic specificity of the space that requires that you look at which of your work fits, and maybe less at what you want to show and put in the spotlight.

Lucie: I agree; if we were in a white cube, we would probably have worked together more on concepts. I don’t know. It would have been different right from the beginning, that I am sure of.

Carolin: The corridor makes both works more private, I think, because you don’t have this white cube distance between the works. It rather favoured a conversation between the works.

Lucie: Yes, absolutely, Carolin, and as you say, it’s also very different to come into a room and stand in front of the objects, or to just walk past them as you walk down a hallway and see the objects in passing, from the side, as it happens in this hallway situation.

Heyer: Thank you for all your observations and comments, Lucie, Carolin and Dico, I really appreciated our conversation. And thank you, Kathrin and Marco, for organizing it.

Heyer Thurnheer is a contextual artist, activist and Philosophy of Freedom sociologist with a multimedia art practice. He is a founder and member of various art and education collectives and exhibition-platforms in Switzerland and the Netherlands. His works and writings are shown regularly in non-institutional art spaces and public institutions.