Passages en Passant #6:

Benjamin Earl and Daniela de Paulis

Maart 10, 2023 – April 26, 2023

Het interview

(english below)

door Marie Dicker

Marie: Kenden jullie elkaars werk al voor deze tentoonstelling?

Beide: Nee, helemaal niet

Marie: Dat is verrassend, want jullie werken met overlappende thema’s. Hoe was het om elkaars werk te ontdekken in het begin?

Daniela: Voor mij was het niet verrassend omdat ik deze kruising tussen radiotechnologieën en kunst de laatste jaren steeds meer heb zien plaatsvinden. Ik werk al zo’n vijftien jaar met radiotechnologieën en kunst. Het is dus heel interessant voor mij om te zien hoe kunstenaars deze technologieën nu ontwikkelen

Marie: Dus je ziet dit als een ontwikkeling waarbij mensen steeds meer geïnteresseerd raken in dit onderwerp?

Daniela: Precies. Ik denk dat het nu allemaal samenkomt. Ook vanwege het feit dat er meer

publiek debat is over ruimteverkenning. De afgelopen jaren hebben we meer NASA-beelden gezien en ontdekkingen van exoplaneten en al dat soort dingen. Het wordt in toenemende mate een belangrijk onderwerp. Ik denk dat het een impact heeft op de culturele sfeer.

Ben: Voor mij was het eerder een aangename verrassing om te ontdekken dat iemand anders met radio werkte, omdat ik het zelf nog niet zo lang deed. Ik had er ook nog nooit met iemand buiten mijn naaste omgeving over gesproken.

Daniela: Ik denk dat de voornaamste overeenkomst tussen onze praktijken de technologie is, maar we gebruiken die op verschillende manieren.

We zijn waarschijnlijk twee van de paar kunstenaars in Nederland of Rotterdam die specifiek die met radio en kunst werken. Internationaal gezien is het een behoorlijk groot veld. Door mijn onderzoek ontdekte ik dat dit veld minstens teruggaat tot de jaren ’70, wellicht is het ouder dan dat.

Marie: Mag ik vragen wat jullie interesse voor dit onderwerp heeft gewekt, gezien dat het niet zichtbaar is of iets waarover mensen veel praten? Daniela, van wat ik begrepen heb, ben je ook zendgemachtigde/ radio-operator?

Daniela: Ik ben radio-operator geworden, maar voor mij was het een natuurlijke progressie vanuit andere dingen die ik in het verleden heb gedaan.

Wat me echt geïnteresseerd maakte in deze kruising van radiotechnologieën en kunst was het ontdekken van het werk van een kunstenaar genaamd Pauline Oliveros, die nu overleden is. Zij was een experimentele muzikante.

Ze deed prachtige performances in de jaren ’80. Mensen stonden letterlijk in de rij om te bellen en de echo van hun eigen stem te horen weerkaatsen op het maanoppervlak. De voorstelling heet Echoes from the Moon

Zodra ik dat las, veranderde mijn leven. Ik maak geen grapje. Het is niet overdreven. Het feit dat je een ander hemellichaam kon aanraken met dit instrument, met deze fysieke golven, en de gegevens terug kon ontvangen was een ongelooflijk idee voor mij. Ik besloot om met deze technologie te gaan experimenteren en in 2017 had ik het genoegen om samen te werken met de Pauline Oliveros Trust.

Ben: Voor mij was het toen ik student was en me verdiepte in peer-to-peer technologie. Ik was geïnteresseerd in hoe je informatie tussen elkaar kunt overbrengen. Ik was op zoek op het internet en zocht naar dingen die niet afhankelijk waren van intermediaire verbindingen. Samen met een vriend besloot ik een radiostation op te zetten voor de school, omdat ze geen studenten radiostation hadden. Dus hebben we dit radiostation opgericht om de activiteiten van de studenten te promoten.

Maar ik bleef maar terugdenken aan dat eerste moment van onderzoek naar peer-to-peer technologieën en wat je eigenlijk kunt doen met radio als technologie in plaats van als platform. Toen ontdekte ik de radio satellieten en hoe gemakkelijk het was om ermee te communiceren via eenvoudige radio antennes. Voor mij gaat het allemaal om het ontvangen.

Marie: Als ik het goed begrijp, zit daarin voor jou ook de sociale component van directe communicatie zonder tussenschakels?

Ben: Ja, zoals manieren zoeken om met elkaar te praten. Iets dat niet noodzakelijkerwijs de standaard manier was waarop we tegenwoordig onze technologie gebruiken voor communicatie.

Marie: Wat ik heel interessant vond, is dat jullie werken aan een onderwerp waar het publiek meestal weinig over weet. Hoe ervaar je de interactie met het publiek?

Daniela: In het begin was de grootste verrassing voor mij dat ik me realiseerde dat de meeste mensen het concept van radiogolven niet helemaal begrijpen. Juist omdat het onzichtbaar is. Het is onhoorbaar. Het is onwaarneembaar.

Mensen hebben echt moeite met het begrijpen van wat je doet. Ik heb geprobeerd om ook een publiek van buiten de kunstwereld erbij te betrekken. Het was echt een uitdaging om deze concepten uit te leggen.

Ben: Het is interessant om te denken dat, ondanks de lange geschiedenis van de combinatie van radio en kunst, er de laatste tijd steeds minder gebruik wordt gemaakt van radio omdat digitale technologie het vervangt.

Wanneer het gaat over reacties van het publiek is het ding dat het meest ter sprake komt wanneer ik vertel dat het om een analoge technologie gaat. En dan hebben ze zoiets van: Wat? Hoe kan het analoog zijn? Het is een signaal, het is transmissie, het is digitaal, toch?

En dan leg je het verschil uit tussen analoge en digitale signalen. Dan vertel je ze over de golven, zoals je zei. In een digitale wereld ben je verbonden of niet verbonden.

Maar met een analoog signaal kun je daar ergens tussenin zitten, verbonden én niet verbonden. De ruis wordt dan een onderdeel van het beeld zelf, of van het signaal.

Daniela: Het is interessant om te zien hoe deze werkelijk alomtegenwoordige technologie zo weinig wordt begrepen en zelfs niet besproken wordt. Radiogolven zijn een krachtig communicatiemiddel, niet alleen voor radio-uitzendingen zoals FM of andere typische radio-uitzendingen. Een van de grootste culturele revoluties, het begrijpen van kosmische verschijnselen, vindt plaats dankzij radio.

Ter voorbeeld, zowel NASA als ESA (het Europees Ruimteagentschap) communiceren met hun ruimtevaartuigen via de radio.

Ze zenden een signaal om een opdracht naar de rover op Mars te sturen en deze voert de verzonden opdracht uit. Vervolgens stuurt de rover de beelden of geluiden die hij op de planeet heeft verzameld terug. Zo ontvangen we al deze verbluffende beelden. Dankzij radiogolven.

Marie: Je hebt boodschappen naar de Maan gestuurd, maar je hebt ze ook ontvangen, als echo’s. Hoe was het de eerste keer dat je dit voor elkaar kreeg?

Daniela: Het is verbazingwekkend om je eigen stem via de maan weerkaatst te horen. Het heeft een indrukwekkende verbeeldingskracht. Ik begon met het organiseren van wereldwijde performances via het internet waar mensen beelden naar de maan en terug konden sturen of de echo van hun stem konden horen. Dat is behoorlijk transformatief. Ik denk dat iedereen het op een andere manier ervaart. Na de voorstellingen kreeg ik berichten van mensen van over de hele wereld die me vertelden wat ze dachten. Zoals Ben al zei, heeft het medium zelf een enorm sociaal potentieel, omdat het zo’n cultureel en technologisch hulpmiddel is.

Ben: Om terug te gaan naar je eerste geval eureka-moment, het terugkaatsen van je stem. Dat komt omdat het doen van dit soort dingen iets tastbaars maakt. Je begint het te begrijpen. Zodra je eenmaal begint iets te voelen dat normaal onzichtbaar is, dan klikt er op de een of andere manier iets in je hoofd. Er stuiteren dingen buiten rond en je kunt er gewoon naar luisteren of je kunt het beginnen te begrijpen met de zeer minimale middelen van een antenne en een luidspreker.

Daniela: Voor mij was het de fascinatie om iets aan te kunnen raken met dit verlengstuk van ons lichaam of geest. Radiogolven zijn een uitbreiding van het menselijk lichaam, de menselijke geest; we kunnen veel verder reiken met de snelheid van het licht, waar dan ook in de kosmos.

Marie: We hebben het een beetje gehad over je interactie met het publiek. Heb je het gevoel dat het publiek echt begrijpt waar de werken over gaan? Want in deze tentoonstelling loop je door de gang zonder enige informatie. Vind je de reacties na de uitleg fijn?

Ben: Dat zijn eigenlijk twee vragen. De tentoonstellingsruimte zelf is misschien niet super beschrijvend. Misschien is dat ook wel de bedoeling. Maar toen het aankwam op de workshops – mensen naar de satelliet laten luisteren en zich voorstellen dat die ergens boven onze hoofden zweefde. Toen begonnen mensen te zeggen: Ik krijg een raar gevoel wanneer ik me voorstel dat er iets is 800 kilometer boven mij. Op dat moment klikt er iets en begin je jezelf te zien als een verbonden persoon in dit hele web van alles.

Marie: Ik had het geluk om bij een van je workshops te zijn. Je vraagt mensen om te gaan zitten of liggen of gewoon te luisteren voordat ze verbinding maken met de satelliet. Is dit om ze wat te laten aarden?

Ben: Ja, precies. Je moet een tegenwicht bieden aan wat er gaat gebeuren. Ik vond het eigenlijk desoriënterend om naar iets te luisteren dat zo ver weg is. Je krijgt een vreemd gevoel van de schaal van dit alles en dat moet worden gecontrasteerd met de aarding in waar je op dat moment bent. Vooraf luisteren naar de omgeving kan de desoriëntatie in een context plaatsen.

Marie: Het was heel interessant om te zien hoe het publiek reageerde. Je kunt je richten op de wetenschap, maar jullie zijn kunstenaars die ook een bepaald verhaal vertellen, een bepaald gevoel beschrijven of zelfs gewoon iets poëtisch tonen. Ik denk dat het moeilijker is als je zoveel wetenschap aan mensen moet uitleggen om het ze te laten begrijpen.

Daniela: Ik denk niet dat dit obscuurder is dan elke andere vorm van hedendaagse kunst. Ik bedoel, als je een hedendaagse dansvoorstelling ziet, en je weet niets over dans, dan voelt het heel obscuur – hetzelfde geldt voor een abstract schilderij of zelfs een zogenaamd realistisch schilderij. Die zijn net zo ontoegankelijk als ons werk. Als je alleen de oppervlakte ziet, probeer dan door je gedachten toegang te krijgen tot de betekenis van het werk. Ik denk dat het een oefening is om beter naar onze omgeving te luisteren en te proberen verder te gaan dan de oppervlakte van dingen.

Ben: Het hangt ook af van de persoon. Soms hoef je niet alles te weten over wat er wat er gaande is. Je begint dit soort ‘alledaagse’ technologie te hercontextualiseren en dan te verheffen en je begint de poëzie erin te zien. Je begint los te komen van een oppervlakkige laag van begrip van hoe de wereld werkt. Ook al wordt mijn werk gepresenteerd met veel visuele elementen, is het gedeelte dat ik het meest interessant vind toch het audio-aspect.

Ik denk dat dit ook het bedrieglijke aspect van radio is, want we zien niets en we kunnen daarom op een of andere manier geloven dat er niets is.

Maar als je dan eenmaal luistert, opent het die ruimte voor nieuwe inzichten. Wat ben ik? Wie ben ik? Waar ben ik en waarmee sta ik in contact? Als ik door een ruimte beweeg en als ik een radio aanzet, wat ben ik dan? Wat gebeurt er op dat moment?

Radio heeft altijd een audiocomponent. Nou ja, niet altijd, maar heel vaak heeft het een audiocomponent component die ik erg interessant vind. Audio lijkt een medium te zijn dat niet helemaal dezelfde aanwezigheid heeft als een visueel medium.

Marie: Het kost ook wat tijd om ernaar te luisteren. Het is niet vanzelfsprekend, niet zo in je gezicht als het visuele is.

Daniela: Het ervaren van radiotechnologieën door middel van kunst laat ons misschien wel zien hoe beperkt de wereld die we waarnemen eigenlijk is…. Zoals het luisteren naar een satelliet die boven ons hoofd passeert, die we niet zien, die we niet horen. Het is een manier voor ons om toegang te krijgen tot het idee dat er zoveel meer is.

Je kunt het zelfs uitbreiden naar niet-menselijke waarneming, inclusief insecten. Het deed me beseffen dat de wereld op zoveel verschillende manieren wordt waargenomen en dat wij maar één soort zijn. We hebben een zeer beperkte geest en hulpmiddelen om te zien wat er werkelijk gebeurt. Voor mij is dat eigenlijk een heel waardevol geschenk dat we kunnen krijgen door meer leren over radio.

Marie: Het is ook een geschenk dat je aan de kunst geeft.

Daniela: Dat hoeft niet zo te zijn. Ik bedoel, om eerlijk te zijn zie ik mezelf niet per se als een kunstenaar. Ik weet niet wat ik ben. Ik heb gewoon dit werk geproduceerd. Ik stel graag de grenzen van kunst in vraag. Maar wat is het? Als het de kunstwereld echt op zijn kop zet, dan is dat goed, dat is eigenlijk het beste. Wanneer de maatschappij zo complex en onderling verbonden is, dat het niet zomaar als één ding kan worden bestempeld.

Toen ik in 2009 dit werk met Moon Bounce technologie maakte, vertelde men mij dat het wetenschap was en ik zei: Oké, dat vind ik prima. Ik heb er geen probleem mee. Maakt niet uit.

Het is niet aan mij om te zeggen of het een kunstwerk is. Sommige astronomische beelden zijn net zo krachtig als schilderijen. Er zijn curatoren die zeggen dat de Hubble ruimtetelescoop de meest cultureel relevante beelden van de afgelopen decennia heeft gemaakt. Dat is dus kunst. Een bewustzijn van en aandacht voor visuele taal ruimtevaartorganisaties. NASA heeft bijvoorbeeld een fotograaf in dienst die werkt in het team dat beelden maakt op Mars. NASA is zich dus zeer bewust van de visuele taal van de beelden die ze streamen vanaf het oppervlak van Mars.

Ben: Wat ik me pas onlangs realiseerde over de Blue Marble als afbeelding, is dat Carl Sagan veel werk heeft verzet om ervoor te zorgen dat ze het Voyager-ruimteschip ronddraaiden en die foto van de aarde maakten. Alleen dankzij hem bestaat die foto. Hij begreep dat dit een beeld was dat gemaakt moest worden. Dat het de manier zou veranderen waarop mensen de wereld waarnemen. Hij begreep de kracht ervan, denk ik. Daarom vocht hij er zo hard voor.

Daniela: Ja, de Pale Blue Dot foto, waarschijnlijk de meest raadselachtige foto die we hebben, omdat het echt de aarde laat zien als een heel kleine pixel op de foto. Eigenlijk vertelt het ons dat we slechts een stipje zijn in die hele kosmos. Ik denk dat de culturele kracht van dat beeld niet volledig wordt begrepen. Het is erg moeilijk om er iets zinnigs van te maken, voor onze geest om te verwerken wat het echt betekent.

Ben: Absoluut, toen ik voor het eerst dat beeld kreeg bij mijn satellietopname, zocht ik mezelf erin en natuurlijk kun je jezelf niet zien in deze beelden. Op dat moment was ik in een prachtig gebied in Zwitserland, omringd door bergen en natuur. Een geweldige plek, maar je kon daar niets van zien. Je zag alleen een pixel.

Het maakt gewoon elk soort leven in dat gebied, of waar dan ook in dat beeld, volledig plat. Dus krijg je een gevoel van perspectief. Het geeft je een gevoel van schaal. Hier komt het idee van leven op twee verschillende manieren naar voren: door het te vernietigen, maar ook door de onderlinge verbondenheid…

Op de een of andere manier voel ik de behoefte om tegen dit beeld van bovenaf te vechten. Ik voelde de behoefte om weer leven toe te voegen in het beeld zelf. Op zijn minst om te proberen de activiteit te laten zien die plaatsvindt op het moment dat de satelliet overvliegt.

Kathrin: Voor mij voelde het tijdens je workshop bijna alsof je een gecomprimeerd pakketje dat door de technologie is gemaakt ontvouwde. Ik denk dat dit is wat me intrigeert als bezoeker, dat ik deel kan uitmaken van dat ontvouwen en de mogelijkheid om het samen te lezen of te herlezen.

Ben: Misschien zit er een pedagogisch aspect aan en heeft het een element van delen in een manier om iets te weten te komen of te doen. Ik denk dat de belangrijkste reden waarom ik de workshop wilde doen was omdat tijdens de ervaringen die ik toen had, ik alleen was, luisterend en gebruikmakend van deze hulpmiddelen. Daarna begin je je manier van weten waar je bent en wat je doet uit te breiden.

Toen ik aan het opnemen was, kwamen mensen naar me toe om te vragen of ze naar het geluid van de satelliet konden luisteren. Plotseling werd het sociaal, want je geeft de koptelefoon aan een willekeurig persoon in het park en zij worden deel van dit ding dat verbonden is met de satelliet.

Op het moment dat ze het meemaakten, begonnen ze te begrijpen wat er aan de hand was. Je kunt iemand dit zien doen op het dak, maar je zult nooit echt begrijpen wat het is om dat ding boven je hoofd te voelen als je het niet zelf doet. Je moet het ervaren. Of het nu over het terug zien komen van het ding van de maan, of over het luisteren naar satellieten, of wat het ook is.

Kathrin: Er lijken veel momenten te zijn waarop er tijd verstrijkt tussen verzenden en ontvangen. Ik ben nieuwsgierig naar het begrip van tijd in deze processen waar we het vandaag over hebben gehad, zoals de perceptie van tijd, of wat voor soort invloed tijd heeft in jullie werk.

Daniela: Ik weet nog dat ik deze evenementen tussen de Aarde en de Maan postte. Een van de allereerste vragen was: Hoe lang doet een signaal erover om naar de maan te gaan en weer terug?

Het is twee en een halve seconde – eigenlijk is het de snelheid van het licht, en dat was verbijsterend voor de meeste mensen. Het is iets dat we niet eens kunnen bevatten. Dus tijd is wederom heel anders dan wat wij ervaren. Ik denk dat dit ook heel zichtbaar is in je workshops, Ben.

Ben: Elke keer als we met deze oefening in de workshop beginnen, probeer ik uit te leggen waar de satelliet boven de horizon opkomt, meestal ergens boven Rusland of Finland of Noorwegen, en waar hij gaat ondergaat, ergens over Afrika.

Als je weet dat dit de afstand is die de satelliet in zestien minuten heeft afgelegd en dat de satelliet in minder dan een minuut doet over de afstand tussen Londen en Parijs als hij over ons hoofd vliegt, begin je een gevoel van snelheid te krijgen.

Als de satelliet passeert, duurt het tien tot vijftien minuten om dat volledige beeld te maken. Het beeld zelf lijkt alsof het slechts een momentopname is, maar dat is het niet. In die tijdspanne hebben er veel gebeurtenissen plaatsgevonden. Het is grappig om te bedenken dat dit eigenlijk niet een beeld is van één tijd en één ruimte, maar van vele tijden en vele ruimtes. Het is echt meervormig. Ik stel het me graag voor als meer dan alleen een instrument om met het weer bezig te zijn. Als we beginnen na te denken over ons bestaan en hoeveel miljoenen mensen zich in dat ene beeld bevinden, hun leven leiden, z odra we een gevoel van die schaal krijgen; daar ligt voor mij de poëzie.

Daniela: Zeker, en als je dat doortrekt naar de Maan, heb je deze uitwisseling tussen Aardbewoners en de Maan. Maar in die tweeënhalve seconde is er zoveel gebeurd tussen de Aarde en de Maan. De Aarde heeft om haar eigen as gedraaid, de Maan heeft rondgedraaid en ook geschud, en de radio-operators moeten corrigeren voor al deze veranderingen. Het is een ongelooflijke manier om je verbeelding te verruimen en om te beseffen dat terwijl we ademen, tijdens één hartslag, er al zoveel gebeurt.

Als je het vanuit kosmisch perspectief bekijkt, is niets hetzelfde als een seconde eerder. Bijvoorbeeld, in het geval van mijn foto’s die terugkeren van de Maan, wat ik altijd fascinerend vond is dat zelfs als je hetzelfde beeld meerdere keren weerkaatst tegen het oppervlak van de maan, je een heel ander resultaat krijgt, omdat alles in de tussentijd is veranderd. Het is heel poëtisch en subliem om als mens over al deze fenomenen na te denken.

Er is een heel beroemd schilderij van Caspar David Friedrich van een man die naar een berg kijkt. Het gaat over de relatie tussen de mens en de natuur; het gevoel klein te zijn en ook voor de natuur te staan, getuige te zijn van de natuur, er deel van uit te maken.

Ik denk dat wij mensen onze plaats in de natuur bevragen. Misschien hebben we die plaats overschat.

Marie: Maar dan weet je dat er veel meer is dan alleen de aarde.

Daniela: Ja, absoluut.

Marie Dicker studeerde kunstwetenschappen en archeologie. Ze werkt in de culturele sector waar ze kunstenaars ondersteunt met subsidieaanvragen, het schrijven van teksten, representatie en het concretiseren van ideeën. Daarnaast is Marie actief in het Burgerpanel Rotterdam als bestuurslid.

Overzicht expo met werk van Benjamin Earl

Overzicht expo met werk van Benjamin Earl en Daniela de Paulis

Daniela de Paulis, The Metamorphosis of a Periplaneta Americana, audio installation, 2015-2020

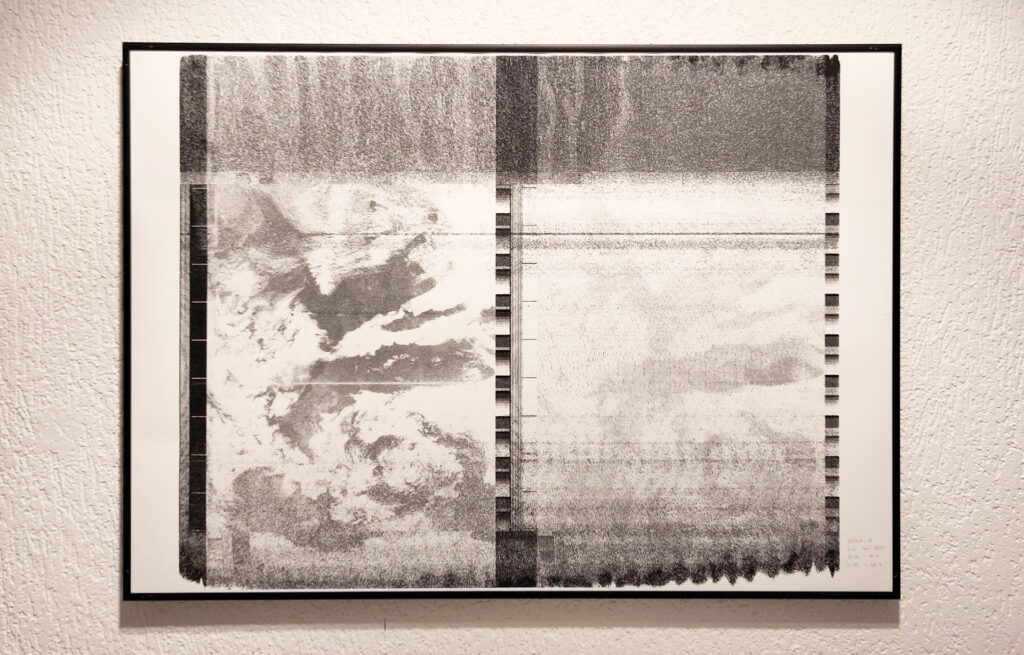

Benjamin Earl, Looking Down, ink on paper, 70x50cm, 2023

Het interview

(english below)

door Marie Dicker

Marie: Did you know each other’s work before this exhibition?

Both: No, no, no, no.

Marie: This is surprising, because you have overlapping themes. What was it like to discover each other’s work in the beginning?

Daniela: For me, it wasn’t surprising because I’ve seen this intersection of radio technologies and art happening more and more over the last few years. I’ve been working with radio technologies and art for about 15 years. So it is quite interesting for me to see how artists are developing these technologies now.

Marie: So you see this as an evolution towards people being more interested in the subject?

Daniela: Exactly. I think it’s all coming together. Also because of the fact that there is a lot more public discussion about space exploration. In the last few years we’ve seen a lot of NASA images and discoveries of exoplanets and all these things. It’s increasingly becoming an important topic. I think it has an impact on the cultural sphere.

Ben: For me, it was more of a pleasant surprise to discover that someone else was working in radio, because I hadn’t been doing it for that long either. Also, I hadn’t really talked about it with anyone outside of my immediate circle.

Daniela: I think the main connection between our practices is the technology, but we use it in really different ways. We are probably two of the few artists in the Netherlands or Rotterdam specifically to work with radio and art. Internationally, it is actually quite a large field. Through my research, I discovered that this field dates back at least to the ’70s, maybe even earlier.

Marie: May I ask what piqued your interest in this subject, since it’s not something that’s visible or that people talk about a lot? Daniela, from what I heard, you’re also a radio operator?

Daniela: I became a radio operator, but for me it was really quite a natural progression from other things I’ve done in the past.

What really got me interested in this intersection of radio technologies and art was discovering the work of an artist called Pauline Oliveros, who is now dead. She was an experimental musician. She did these beautiful performances in the ’80s. People would literally queue up to actually talk on the phone and hear the echo of their own voice reflected off the surface of the Moon. The performance is called Echoes from the Moon.

As soon as I read that, my life changed. I’m not joking. It’s not an overstatement. The fact that you could touch another celestial body with this tool, with these physical waves, and receive the data back was an incredible thought to me. I decided to start experimenting with this technology and in 2017 I had the pleasure to collaborate with the Pauline Oliveros Trust.

Ben: For me it was when I was a student and I was looking into peer-to-peer technology. I was interested in how you can transfer information among one another. I was searching on the internet and doing things that didn’t rely on middleman connections. My friend and I decided to set up a radio station for the school, since they didn’t have a student run radio station. So we set up this radio station to amplify the students’ activities.

But I kept thinking back to that initial moment of looking at peer-to-peer technologies and what you could actually do with radio as a technology rather than a platform. That’s when I discovered these radio satellites, and how easy it was to interact with them through very simple radio antennas. It’s all about receiving things for me.

Marie: If I understand it correctly, for you, it also has the social component of direct communication without intermediaries?

Ben: Yeah, like trying to find ways to talk to each other. Something that wasn’t necessarily the standard way we use our technology today for communication.

Marie: What I found very interesting is that you’re working on a subject that the public often knows very little about. How have you found your interaction with the public?

Daniela: For me at the beginning, the main surprise was to realise that most people don’t quite understand the concept of radio waves. Because it is invisible. It is inaudible. It is not perceptible. People really struggle with the idea of what you’re doing. I tried to involve people who are really not in the art scene at all. It was really challenging to try and explain these concepts.

Ben: It’s interesting to think that, even when it’s got this long history of radio and art together, more recently radio is becoming used less frequently everywhere as digital technologies take over.

When it comes to working with the public the thing that comes up most of the time for me is when I’d say it’s an analogue technology. And they’re like: What? How can it be analogue? It’s a signal, it’s transmission, it’s digital, right?

And then you’re explaining the difference between analogue and digital signals. Telling them about the waves, like you said. In a digital world, you’re either connected or you’re not connected. Whereas with an analogue signal, you can be somewhere in between, connected and not connected. That is where the noise actually becomes part of the image itself, or of the signal.

Daniela: It’s interesting to see how this truly ubiquitous technology is so little understood and not even discussed. Radio waves are a powerful means of communication, not just radio broadcasts like FM or other typical radio transmissions. One of the greatest cultural revolutions, the understanding of cosmic phenomena, is happening thanks to radio.

For example, both NASA and ESA, the European Space Agency, communicate with their spacecrafts by radio. They transmit a signal to send the command to the rover on Mars and it executes the direction that has been sent. Then the rover relays back the images or sounds collected on the planet. That’s how we receive all these amazing images. Thanks to radio waves.

Marie: You have sent messages to the Moon, but you have also received them, like echoes. How was the first time that you managed to do this?

Daniela: When you actually hear your own voice reflected by the Moon, it’s quite amazing. It has a really very impressive imaginative power. I started hosting these global performances via the Internet where people could send images to the Moon and back or hear the echo of their voice. That is quite transformative. I think it’s something which everybody experiences in a different way. After the performances I received messages from people from around the world telling me what they thought. As Ben mentioned, it has a huge social potential – the medium itself, as it’s such a cultural tool, as well as a technological tool.

Ben: Going back to your first instance of having this eureka moment, bouncing your voice back. It’s because doing that kind of stuff makes it tangible. You begin to make sense of it. Once you begin to sense something that is invisible, somehow something clicks in your head. There is stuff bouncing around outside and you can just listen to it or you can begin to make sense of it with the very minimal means of an antenna and a speaker.

Daniela: For me it was the fascination of being able to touch something with this extension of our body or mind. Radio waves are an extension of the human body, the human mind; we can reach much further at the speed of light anywhere within the cosmos.

Marie: We talked a little bit about your interaction with the public. Do you feel that the public really understands what the works are about? Because in this exhibition you walk through the hallway without any information. Do you enjoy the reactions after an explanation?

Ben: There’s kind of two questions there. The exhibition space itself might not be super descriptive. Maybe that’s the point, in a way. But then when it came to the workshops – getting people to listen to the satellite and imagine that it was floating somewhere above our heads – that’s when people began to say: I get a weird feeling when I imagine that there’s something above us 500 miles away from me. It’s in that moment that something clicks, and you begin to see yourself as a connected person in this whole web of everything.

Marie: I was lucky enough to be at one of your workshops. You ask people to sit or lie down or just listen before they have this connection with the satellite. Is this to give them some grounding?

Ben: Yeah, exactly. You need to supply a counter to what is going to happen. I actually found it disorienting listening to something so far away. You get this weird sense of scale that needs to be contrasted with a grounding of where you actually are at the moment. Listening to the surrounding environment beforehand enables a contextualisation of the disorientation.

Marie: It was very interesting to see how the public reacted. You can focus on the science but you’re artists who are also telling a certain story, describing a certain feeling or even just something poetic. I think it’s difficult when you have to explain so much science to people to make them understand.

Daniela: I don’t think this is more obscure than any other form of contemporary art. I mean, if you see a contemporary dance performance, and you don’t know anything about dance, then it feels very obscure – the same with an abstract painting or even a so-called realistic painting. It is just as inaccessible as the work that we do. If you only see the surface of it, in your mind, try to access the meaning of the work. I think it’s an exercise of listening to our surroundings better and trying to go beyond the surface of things.

Ben: It also depends on the person. Sometimes you don’t need to know everything about what’s going on. You begin to recontextualise this kind of ‘mundane’ technology and then begin to elevate it and you begin to see the poetics within it. You begin to break away from this surface layer of understanding of how the world works. Even though my work is presented with a lot of visual elements, the part that I find most interesting is somehow the audio aspect. I think that’s also the deceptive part of radio, because we see nothing and we can somehow believe that there is nothing there. But then once you listen, it opens up that space for new understandings. What am I? Who am I? Where am I and what am I interacting with? When I move through a space and when I turn on a radio, what am I? What’s going on at that moment?

Radio always has this audio component. Well, not always, but quite often it has this audio component to it that I find very interesting. Audio seems to be this medium that doesn’t quite have the same presence as a visual medium.

Marie: It also takes some time to listen to it. It’s not that obvious, not so much in front of your face as the visual is.

Daniela: Perhaps experiencing radio technologies through art really shows us how the world we perceive is actually very limited. For example, listening to a satellite passing overhead, which we don’t see, we don’t hear. It is a means for us to access this idea that there is so much more. You can even extend it to non-human perception, including insects. It made me realise that the world is perceived in so many different ways and we are only one species. We have a very limited mind and tools to see what is really happening. To me, that is actually a quite precious gift we can get from learning more about radio.

Marie: It is also a gift that you give to art.

Daniela: It doesn’t have to be. I mean, to be honest, I like to think of myself not necessarily as an artist. I don’t know what I am. I just produced this work. I do like to question the boundaries of art. What is it? If it really unsettles the art world, that’s good, that’s actually the best part. When society is so complex and interconnected, it cannot just be labelled as one thing.

I mean, when I was making this work with Moon bounce technology in 2009, I had people telling me that it was science and I said: Okay, I’m fine with that. I have no problem. Whatever.

It’s not up to me to say if it’s a work of art. Some astronomical images are as powerful as paintings. There are curators who say that the Hubble Space Telescope produced the most culturally relevant images of the current decades. So that is art. An awareness and attention to visual language by space agencies. For example, NASA employs a photographer who works in the team that takes images on Mars. So NASA is very aware of the visual language of the images they stream from the surface of Mars.

Ben: What I only realised very recently about the blue marble as an image, is that Carl Sagan went through a lot of work to make sure that they turned the Voyager spacecraft around and took that photo of Earth. It was only because of him that that image exists. He understood that this was an image that needed to be made. That it would change the way that people perceive the world, in a certain sense. He understood the power of it, I think. Which is why he fought so hard for it.

Daniela: Yeah, the Pale Blue Dot image, probably the most enigmatic image we have, because it’s really showing the Earth as a very small pixel in the photo. Basically, it’s telling that we are just a speck in all of that cosmos. I think the cultural power of that image is not fully understood. It’s really very difficult to make any sense of it, for our minds to process what it really means.

Ben: Completely. When I first got that image on my first satellite listening, I was looking for myself in it and of course, you can’t see yourself in these images. At the time I was in this beautiful area in Switzerland surrounded by mountains and nature. An amazing place, but you couldn’t see any of that, you saw nothing. You just saw a pixel.

It just completely flattens any kind of life that was in that area, or anywhere within that image. So you do get this sense of perspective. It gives you a sense of scale. This comes out the idea of life in two different ways: of destroying it, but also showing its interconnectedness. I somehow feel the need to fight against this image of top down. I felt the need to add life back into the image itself. At least to try to show the activity that goes on during that moment when the satellite flies over.

Kathrin: For me, during your workshop, it felt almost as if you were unfolding the compressed package made by the technology. I think this is what makes me intrigued as a visitor, I can be part of that unfolding and the potential of reading or rereading it together.

Ben: Maybe there’s a pedagogical aspect to it, an element of trying to share a way of knowing or doing something. I think the main reason I wanted to do the workshop was because in the experiences I’ve had before, I was just by myself, listening and using these tools. Then you begin to expand your way of knowing where you are and what you’re doing.

When I was recording, people would come up to me and ask to listen to the sound of the satellite. Suddenly it became social, because you would give the headphones to some random person in the park, and they would become part of this thing that was connected to the satellite. In that moment of experiencing it, they actually began to understand what’s going on. You can see someone doing this on the roof, but you’re never going to really understand what it is to feel that thing passing over your head unless you’re also there doing it. It has to be experienced. Whether it’s about seeing the thing come back from the Moon, or whether it’s about listening to satellites, or whatever it is.

Kathrin: There seem to be a lot of instances of time passing between sending and receiving. I’m curious about the understanding of time in the processes that we’ve been speaking about today, like the perception of time, or what kind of agency time has in your work.

Daniela: I remember when I used to post these events between the Earth and the Moon. One of the very first questions was: How long does it take for a signal to go to the Moon and back?

It’s two and a half seconds – basically, it’s the speed of light, and that was mind-blowing for most people. It’s something we can’t even fathom.

So time is again, very different from what we experience. I think this is also very visible in your workshops, Ben.

Ben: Every time we start the exercise in the workshop, I try to explain where the satellite is going to rise, over the horizon, usually somewhere over Russia or Finland or Norway, and where it’s going to set, which is somewhere over the top of Africa.

Knowing that is the distance travelled in 16 minutes, and that the satellite flies past our heads in less than a minute between like London and Paris, you begin to get a sense of speed. As the satellite passes over, it takes 10 to 15 minutes to make that full image. The image itself looks like it’s just a snapshot, but it’s not. Many events have occurred within that time period. It’s funny to think that actually this is an image not of one time and one space, but of many times and many spaces. It’s really multifaceted. I like to imagine it as not just a tool to engage with the weather. We begin to think about our existence and how many millions of people are in that one image, living their lives, as soon as we get a sense of scale; I think that is where the poetics lie for me.

Daniela: Definitely, and when you extend that to the Moon, you have this interaction between Earthlings and the Moon. But in those two and a half seconds, so much has happened between the Earth and the Moon. The Earth has been spinning on its own axis, the Moon has been rotating and also shaking, and the radio operators have to correct for all these changes happening as we speak. It’s an incredible way to expand your imagination and to realise that while we breathe, during one heartbeat, a lot is going on.

If you look at it from the cosmic perspective, nothing is the same as a second before. For example, in the case of my images returning from the Moon, what I used to find captivating is that even reflecting the same image off the surface of the Moon several times, you will get a completely different result, because everything has changed in the meantime. It’s quite poetic and sublime to think about all these phenomena as a human being.

There is this very famous painting by Caspar David Friedrich of a man looking at a mountain. It’s about the relationship between humans and nature, and this feeling of being small and also being in front of nature, being a witness to nature, being a part of it. I think we as humans are questioning our place in nature. Maybe we have overestimated it.

Marie: But then you know that there’s much more than only Earth.

Daniela: Yeah, absolutely.

Marie Dicker studied art science and archaeology. She works in the cultural sector where she supports artists with grant applications, writing texts, representation and concretisation of ideas. In addition, Marie is active as a board member in the Rotterdam citizens’ panel .